Reports have arisen this week highlighting the eating disorder epidemic in the United Kingdom, with some statements claiming that admissions have risen nearly 90% in half a decade. This unprecedented rise, again, is against the spectre of coronavirus hospital pressures and a health service on its knees. The current surge in new eating disorder admissions is particularly troublesome amongst men, but more concerningly, young boys. The rate for this population has increased well over 100%, and by March 2022 there were 10,000 active cases receiving treatment in the NHS – smashing previous records. Earlier this year, the NHS federation pledged to increase mental health service funding for young people by £79 million and hopes to see more individuals coming forward for help by years end. The question is, why is this condition booming now, and why are almost 2000 more individuals expected to come forward for treatment by the end of 2022?

The term ‘eating disorder’ has been thrown around and lost its central meaning in society, mostly to do with media representation, film and TV depiction and glorification of some social media websites. This can devalue the experience of people who are clinically very ill and struggling every day to control urges and stay healthy. To continue, we must first address the most common types of eating disorders treated in outpatient services;

Anorexia (nervosa): controlling weight through not eating enough or exercising excessively to control weight

Bulimia: feeling out of control with what you eat and then taking action to purge food or drink

Binge Eating (binge eating disorder): eating large portions of food over and above what you need and feeling uncomfortably full or sick following

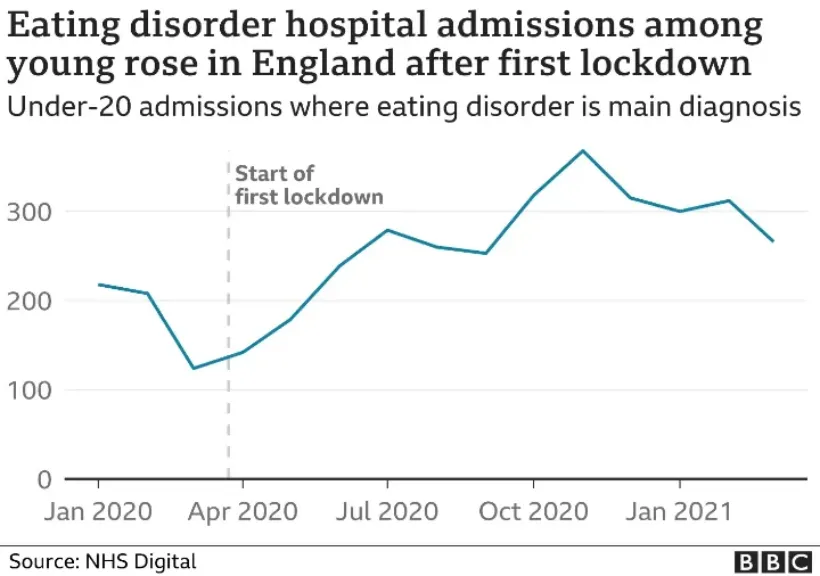

In deciphering the links and causes, one often comes up against a socio-cultural, psychological and physiological dilemma, wherein all factors are inextricably linked. No doubt that for the last two years, many children have been forced inside because of COVID-19, significantly reducing their social contact and thus space to learn and grow with the outside world. After the acute phase of COVID-19, it was reported that 1 in 5 children in the UK were self-harming and experiencing mental health struggles amidst restrictions. Prof Chitsabesan, Clinical Director for Children’s Mental Health in the NHS, noted, “Young people’s problems with food can begin as a coping strategy or a way of feeling in control but may lead to more restrictive patterns of eating and behaviours. The rise could be attributed to the unpredictability of the COVID-19 pandemic, feeling isolated, disruption to routines and experiences of loss and uncertainty”.

Often, weight becomes one of the variables that can be controlled by an individual, and those who have a lack of control due to unemployment, body image issues, a small support network or an established mental health issue nevertheless find eating, diet and weight one of the things they can take back into their own autonomy. This is where the disorders begin to develop and it is not an analogue ‘0 – 1’ state – individuals can display varying signs of disordered eating way before they begin to qualify as an established diagnosis – just in the way clinically well adults have good days and bad days with their mood, for example. For children and adults, weight might have been the only sign of control they had in the background of ongoing restrictions, uncertainty and existential angst that COVID-19 gave to so many.

One does ponder a question, though. Is there now a higher prevalence of eating disorders, or has the mental health taboo in the UK begun to lift? Certainly, in the last decade there has been a considerable shift in the acceptance of mental health conditions due to societal change, social media and many high-level celebrity figures coming out to talk about their own struggles with depression and anxiety. So, is it a case that people now feel they won’t be judged if they present to mental health services to begin to access treatment? With men, in particular, there has been decades of suffering in silence which unfortunately has lead to the increase in suicide, with suicide being the most likely cause of death for adult males between 18 and 50 years of age.

Andrew Gregory, of The Guardian, noted that, “Even when seriously unwell, people with eating disorders can appear to be healthy, with normal blood tests, the college said. For example, somebody with anorexia can have dangerously low levels of electrolytes such as potassium that are not reflected in blood tests. Patients with bulimia can also have severe electrolyte disturbances and stomach problems but can be a normal weight or overweight”. Thus, it is common to overlook these patients as they do not look conventionally ‘seriously clinically ill’ on presentation to emergency departments.

It seems a perfect storm of isolation, social anxiety and little control over our own lives has affected everyone across the spectrum, and one expects to see similar rates of mental health issues and service acquisition with substance use disorders, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. The libertarian stance of people having their own autonomy to enact change might be useful for adults, but what can be done to protect younger children? Prof Chitsabesan continued, “some of the signs to look out for included behaviours such as making rules about what or how they eat, eating a restricted range of foods or having a negative self-image about their weight and appearance”.

Parents, friends and family can look for signs of eating disorders in others such as (provided by NHS England);

dramatic weight loss

lying about how much they've eaten, when they've eaten, or their weight

eating a lot of food very fast

going to the bathroom a lot after eating

exercising a lot

avoiding eating with others

cutting food into small pieces or eating very slowly

wearing loose or baggy clothes to hide their weight loss

A conversation with NHS 111 or GP can facilitate an assessment for you or someone you know, and treatment and help is out there to be accessed.